The command post at any working incident is a busy place. And if you are the one who has spent some time in the “hot seat,” you know how fast the event unfolds, how many more questions you initially have than answers, how many people are relying on you for direction, and maybe even how many show up to “do it their way.”

I showed up at a fire one night where the IC, one of the more polished I had ever worked with, was having one of those nights. The call was not going horribly, but it was also not going like the clockwork we had been working so hard to achieve. The “fire control technicians” (to quote a phrase from the late Chief Alan Brunacini) seemed to be off their game. The reasons why are infinite, but suffice it to say, the IC had his hands full.

When I arrived on scene, I asked him how things were going. He looked at me with that piqued exasperation all ICs have felt at times when the execution isn’t going as planned and said, “Chief, I’m just trying to put the marbles back in the bag.” That simple observation and statement served as a point to announce a reset, inside the command post and outside, and helped get the incident on a path where the fire went out, no one was injured, and there was ample fodder for post-incident learning.

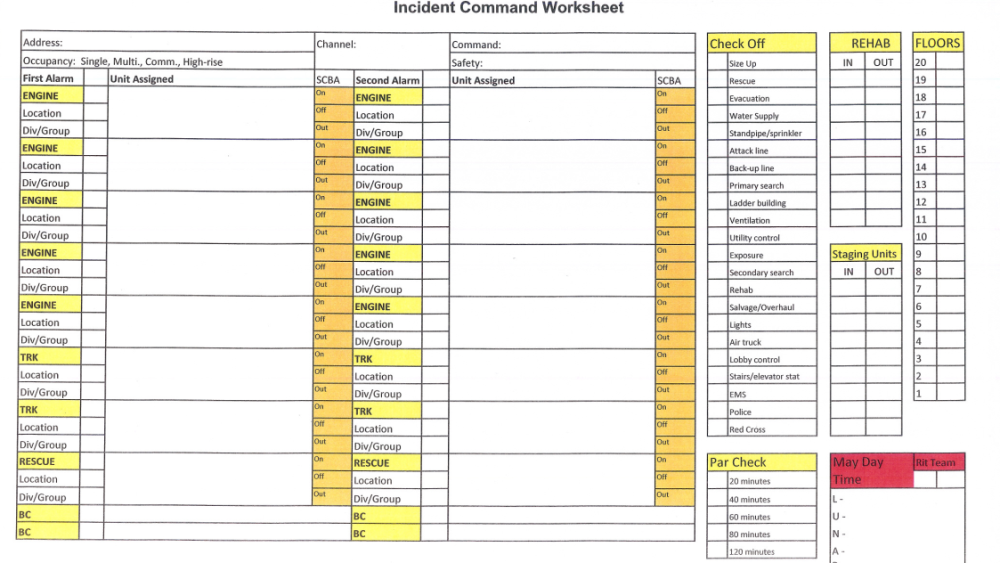

One of the most important tools in the IC’s armory that night in getting through the battle fog was his diligent use of a tactical worksheet. The worksheet he propped up on the steering wheel was his way of bringing order to the chaos, and the step he took numerous times to ensure the safety of his people and everyone in the automatic-aid group.

I found as I advanced into the role of battalion chief and above, command tools were just as critical as PPE and SCBA for interior attack, a patent water supply, coordinated ventilation, and a TIC to find victims or see flashover developing. Where the tools of the trade made the fire go out faster and safer, an IC’s tools were critical to “keeping the marbles in the bag.” But not everyone in the world of command shares that philosophy, and I submit that they are setting themselves up for failure, if not disaster.

Real-world command tool use

The recent FireRescue1 survey of ICs from career, volunteer (including paid on-call) and combination departments returned some interesting data. Of the 1,922 respondents, 63% used a paper command tool, and 7% use an electronic tool. That is good news for the 70% of the firefighters showing up on those incident scenes. However, 30% of the ICs surveyed reported they didn’t use any command tool (defined as a checklist or chart) to manage their incidents. These respondents included representation from all types of fire department organization, with roughly the same number of career (218) and volunteer (212) ICs reporting not using any type of tool.

The survey delved into several other areas to reveal some remarkable data about rank and service time. As one would surmise, chief officers and company officers were the predominate users, and non-users, of a tool. The percentage of users versus non-users held true throughout the ranks, suggesting a consistency of thought among the groups: If you were trained to use a command tool, you use one. If you have not been trained to use a command tool, you don’t.

The service time data produced a telling fact about command tool use. Respondents with 2-5 years of IC experience had the highest percentage of non-tool users than any other service time group. Additional study is warranted to find out the “why,” but taken at face value, ICs with the least experience at command may be the most vulnerable to failure if they are not properly equipped to manage the incident.

Conversely, ICs with 10-20 years, 21-30 years and 30+ years were the highest percentage users, with the 30+ years group exceeding the non-tool users by more than 2:1. Again, more digging is warranted, but is there an opportunity (and dare I say, an obligation) here for senior ICs who use a tool to mentor the less experienced ICs.

Decision-making under stress

The survey is an objective reflection of who we are as a profession. Behaviorists who study humans have clearly defined what happens when we operate under acute stress. We get a flood of adrenaline. Our heart rate and breathing increase. Visual and cognitive focus narrows (as in things start to get by us), and even our hearing can be impaired. Even well-seasoned ICs are not immune to these physiological and psychological reactions of the body, but the astute ones learn (through sets and reps simulations conditioning, objective after-action reviews, and constant learning) to recognize these reactions and keep them at bay or compartmented so they can stay oriented to the tasks at hand.

One of the ways to offset the effects of acute stress is to keep the brain focused on tasks. In order for the IC to start getting the marbles back in the bag, a command tool like a checklist, chart or tactical worksheet, whether paper or electronic, has a vacuum cleaner effect on:

- Restoring order;

- Tracking and achieving tactical objectives; and, most importantly,

- Keeping firefighters as safe as possible as they engage in their high-risk work.

Fortunately, the majority of ICs in the survey either consciously, or unconsciously, have recognized the advantage of a tool to harness the challenges of incident command. And for the one-third of the respondents who use no technology at all, the natural question to ask is simply, “why?” The answers should be revealing.

Final thoughts

Remember, the untaxed human mind can remember seven to 10 facts with relative ease for a short period of time. But the emergency scene is anything but untaxing – and there’s far more than seven to 10 tasks to manage. The flurry and fury of a working fire, vehicle extrication with a trauma patient, uncontrolled hazmat release or wildfire doubling in size every hour stresses the IC in ways few can understand until they have been through it themselves. And once you’ve been through it, you know the importance of a good command tool.

Resource Download

A simple incident command worksheet can serve as your fireground tool

Given all the research into decision-making under duress, it’s vital that ICs have a command tool at the ready