By Michael Buckheit

It’s been 20 years, hard to believe.

Have we forgotten? No! We haven’t forgotten. For those of us who lived through the events of that day, regardless of your career, we all know exactly where we were and what we were doing. I’m sure those thoughts are running through your mind right now.

I’m not alone. We all, in some way, re-evaluated life after 9/11. The love of country was palpable, yet we all felt a sense of loss, a need to find a path forward. For me personally, I felt a drive to somehow, in my small way, make a difference.

No longer our small world

Twenty years ago, I was an FDNY lieutenant in Manhattan. My world revolved around the members of my firehouse. Senior members helped in all aspects of daily firehouse life. We responded together, looked out for each other, and did our best to protect the citizens of New York City.

When it came to support services, most aspects were handled by the many and varied civilian employees of FDNY. If a piece of equipment broke, simply request a new one. If the firehouse needed repairs, send a repair request. And after well over a century at work, this process had become a well-oiled machine. We had the personnel, tools, equipment and staff to do almost anything.

On September 11, 2001, the world changed. A devastating hit, we were rocked. The firehouse was no longer our small world. We began to look outward. An act of terrorism forever changed how we would view our role and respond. Preparedness for large-scale events was the priority. Our well-oiled machine suddenly needed to be expanded, retooled, and capable of addressing “all hazards” in a new and dynamic world to include acts of terrorism.

Combating Terrorism Center

In February 2003, FDNY partnered with West Point to roll out the Combating Terrorism Center. By this time, I was a newly promoted captain, and I applied to attend the Counterterrorism Leadership Program. To be honest, I didn’t think I stood a chance at being selected. It was the first such program being offered, I was a little fish in a big pond, but I wanted to be part of it.

My previous employment had been with Brookhaven National Laboratory Police, charged with protecting the scientific community, plus the site’s High Flux Beam Reactor. Prior to that, I had been a part of the first armed nuclear security team at Shoreham Nuclear Power Station in New York.

These previous jobs created quite a resume apparently, and I was fortunate enough to be selected as one of just over 30 people to be a part of the Counterterrorism Leadership Program. Little did I know that it was this opportunity that would change my path forward to a completely different aspect of FDNY preparedness and response.

New vulnerability

One of several potential projects we had to choose from as part of the course was Harbor Security. It intrigued me. I often heard people say right after 9/11, “Who would have thought they would have used planes as bombs?” I recall thinking of the Kamikaze pilots, in essence, a smart bomb of sorts – simple but effective.

Air travel changed forever after 9/11, but would harbor security?

Great cities throughout history have been built on accessible harbors. Was that now our weakness? Our ports are critical infrastructure, the lifeline for goods to keep this nation supplied. “Never Fight the Last War” was a phrase I always remember from the class. We needed to stay one step ahead and consider how to protect our ports. Marine Operations began looking at how the military stayed adapted to different environments as a guide for how it could be “Fast, Powerful and Agile” in its protection of the waterfront.

Career shift

I was honored to have worked alongside some amazing folks in that course – people who worked tirelessly to plan and rebuild so the department could be resilient and flexible.

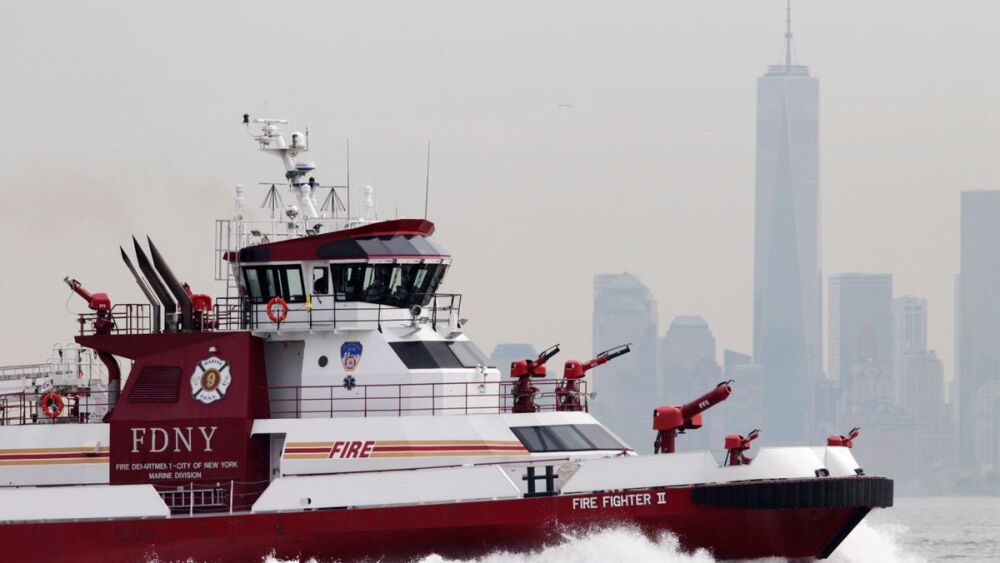

Our working group put forth a report that was reviewed and embraced by FDNY Leadership. FDNY Marine Operations was a shadow of its former glory. The personnel, while dedicated, were left with antiquated equipment and had become almost irrelevant.

Promotion to battalion chief pending, I wouldn’t be assigned in a firehouse; I’d be a covering chief. What’s more, I needed a project. I needed to make a difference. From a personal standpoint, that’s how I felt I could honor those that we lost on 9/11. Everyone has their own way; this was mine.

I started inquiring about some roles that were a bit out of the box. I wanted a challenge. I spoke with someone at Hazmat Operations, but I had a relative there and thought perhaps it was too close. My relative mentioned Marine Operations and how Chief James Dalton was up to his elbows in alligators trying to rebuild the unit.

I reflected on the project with West Point. Harbor security for FDNY Marine Ops was a part of the job that many knew little about, and what they did know was that when Marine was requested, it seemed they would never get there. Through no fault of the members of Marine Ops, the entire Division was a lesson in failure to adapt to a new and changing environment. The harbor had moved from bulk goods storage and manufacturing to a fast-paced, containerized and recreational port.

Rebuilding the unit

As a newly assigned battalion chief, I was assigned to the Marine Battalion – a battalion of one. I worked with Chief Dalton, a lieutenant executive officer and a small support staff.

Two large platform fireboats were in design stage, and a committee had traveled near and far to glean information from other fire departments and incorporate best practices and lessons learned. Our facilities had gone beyond their respective usefulness and were in disrepair. We couldn’t haul a boat at an FDNY facility. We only had diesel fuel available (and a limited amount) at our facility and no gasoline for the smaller boats. Hauling boats required us to go to an oil facility “down the block” at high tide only. We could only haul our small craft, many of which were hand-me-downs from other agencies in ill repair. For our one mid-size boat, we would rely on marinas when available to provide the haul out.

We had a long path ahead – the longest journey begins with but a single step. Step 1: Start with the foundation, then build the house.

We needed a starting point. We knew we couldn’t do it alone. The Port is a close-knit community, and we needed to become a much greater player in port partnerships. Together with partner agencies, we are all capable of far greater accomplishments – MISSION FIRST!

Ideas are wonderful, but without funding, they sit idle on a desk. We needed define who we were, why it’s a critical component of FDNY’s mission while also laying out a strategy and identifying funds. All of this while simultaneously trying to run a Division and Battalion responsible for responding to approximately 560 miles of coastline and countless high-value critical structures.

The U.S. Coast Guard’s Area Maritime Security Committee turned out to be a major step in the right direction. As the Federal on Scene Coordinator, they are a key player in all aspects of our responses. The USCG does a fantastic job at helping to identify available assets and leveraging those assets to meet the challenge at hand.

The FDNY was both honored and proud to have joined this team and to work alongside all our Port of New York and New Jersey partners. It was this partnership that allowed FDNY to be intimately involved in building a more “Fast, Powerful and Agile” fleet to meet the ever-changing needs of the port. Port Security Grant dollars allowed ideas and solid planning to become real, actionable and measurable successes. The value of the Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) to the overall protection of the Port of New York and New Jersey is immeasurable.

Marine Operations today consists of a tiered vessel response matrix, a fully equipped and functional maintenance shop, a 50-metric ton travel lift and finger piers for haul-outs, a negative forklift, a vessel repair building, new firehouses for Marine 1 and Marine 9, new vessel berthing facilities for Marine 1, 6 and 9, a shipboard simulator and damage control simulator, and members trained as Marine Firefighters.

Put it on paper

Through FDNY’s Center for Terrorism and Disaster Preparedness, we were invited to partner with students from the Harvard Business School to write a “Marine Operations Strategic Plan.” We jumped at the opportunity. How could we expect support and funding when we hadn’t a clear path forward? It was our responsibly to define Marine Operations, why we mattered and how we planned to be a part of a much greater role in the safety and security of our port community going forward.

Looking back

I’m retired now. I still keep in touch with several folks within FDNY Marine Operations. I speak often with the current chief of Marine Operations, Chief Frank Simpson, and the Marine Battalion Commander, Chief Joe Abbamonte. To say I’m proud of them for continuing to evolve, lead from the front, and influence positive change is quite an understatement. I feel like a proud parent when I look at Marine Operations. The tremendous amount of work put forth by countless folks of all ranks and within our civilian support services was Herculean.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the members of FDNY Marine. Change is difficult, the many and varied projects unfortunately didn’t allow us to communicate with the boots on the deck members as we would have liked to, and as we should have. I regret that. At the end of the day, it was our members who made these changes possible for Marine Operations. Boats and buildings are just boats and buildings. The most important change was our members embracing change in order to better serve those whom we are charged to protect.

About the Author

Battalion Chief Michael J. Buckheit retired from the FDNY as Chief of Marine Operations, having served the Department for 31 years. Chief Buckheit began his fire service career in 1988 as a firefighter working for Engine Company 72 in the Bronx. He later served as a lieutenant and captain, and was ultimately promoted to battalion chief in the Marine Battalion and later a Marine Battalion Commander.