Retired FDNY Firefighter Lee Ielpi had been working the pile for three months. Along with countless other firefighters, volunteers and other workers, Ielpi slogged through the wreckage. He was there for recovery – any body part, any item of significance to the families of the individuals murdered on September 11. But mostly, he was looking for his son.

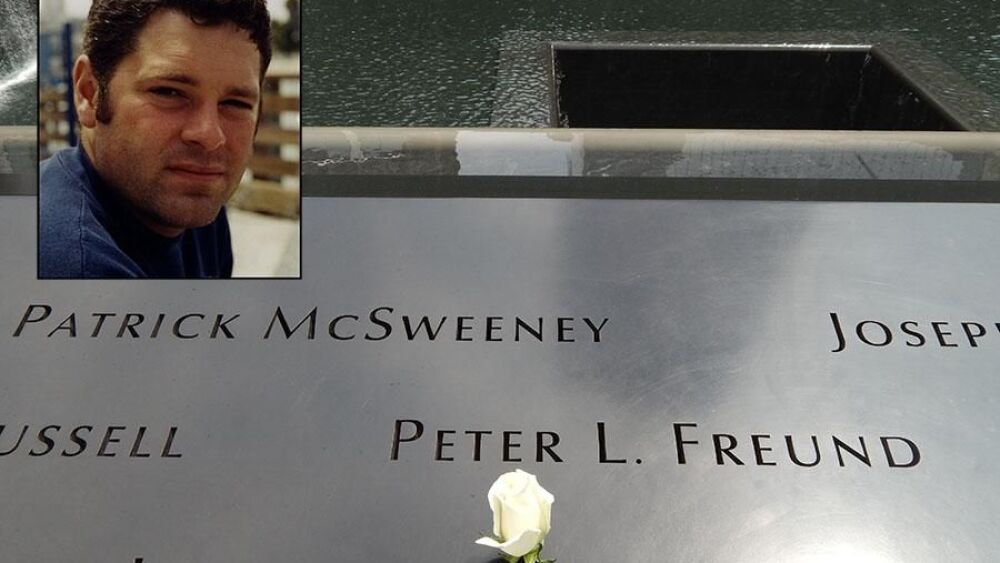

Jonathan Ielpi, a firefighter with Squad 288, was killed in the collapse of the Twin Towers. The entire squad gone.

Amid his work to capture and memorialize World Trade Center steel, Ielpi searched for Jonathan.

Family intuition

On Dec. 11, after another long day of searching the pile, Ielpi decided around 9:30 p.m. to head home to Long Island. At 11:30, now at home, the phone rang. It was the deputy chief in charge of the recovery site for the night.

“And with a very pleasing voice, a happy voice, he said, ‘Lee, we got Jon.’”

He had been waiting for this moment, news he could bring his son home.

Ielpi was preparing to drive back into the city when an unexpected visitor arrived at the house.

“It’s maybe 12 o’clock and who walks in the door but Brendan,” Ielpi recalls of the surprising sight of his other son, an FDNY probationary firefighter. “Now I’m not overly religious by any stretch. I believe in God … but Brendan was living over in another town. He walks in the door, and I look at him and said, ‘What are you doing here? Did you hear?’ He said, ‘No, I didn’t hear anything. I just felt like I wanted to leave the house and come into Great Neck; I just felt like I had to come in.’”

Ielpi told Brendan the news about his brother, and they headed to Manhattan.

“It was a very mixed emotion,” Ielpi recalled, “because now the wife and the kids all realize that we’re going to be bringing Jonathan home, and then driving in and trying to just prepare yourself for what it’s going to be. How is he? It was a very difficult ride-in.”

‘The Band of Dads’ search the site

Ielpi had been searching the site with a group dubbed “The Band of Dads” – eight FDNY fathers looking for their sons. There were lots of dads working at the site, not just these eight, of course, and there were also sons looking for their fathers, for their brothers or other relatives. This particular group of eight, however, knew each other well and would meet up for their searches. All the dads except one were retired.

“We had basically carte blanche from the fire department,” Ielpi explained of their freedom at the site. “We could freelance more than the regular companies because they had to work as a unit. We worked as a unit, but three of us would go that way, three would go this way. We knew what the job was for the day because every morning and in the evening, there’d be a meeting where we’re going to concentrate our work for the day or for the night. We would divide up and the thought was, hopefully, this would be the day we would find one of the kids.”

But any recovery was meaningful, he added: “Anybody we found along the way was going to be a blessing for that family.”

Even after Jonathan’s body was recovered, Ielpi continued coming to the site to search, to support the other dads. “How could I possibly say to the dads, ‘You know, I’ve got my son home. You guys take care.’ That wouldn’t be proper.”

One of the other dads, Captain John Vigiano, lost two children on 9/11 – Joe, a police officer, and John Jr., a firefighter. Only Joe was recovered.

Ielpi felt fortunate in that his son had been recovered – and it wasn’t a body part identified through forensics. It was all of him, still in his turnouts.

“I’m the only one of the dads who was able to bring his son home in one piece,” Ielpi explained. “A couple of dads had their sons brought home in pieces, miscellaneous – isn’t that something, miscellaneous pieces.

Difficult calls from the medical examiner

In the nine months of recovery work at Ground Zero, 20,000 human remains were found.

The Medical Examiner’s office had a system for notifying families about their loved ones’ remains, Ielpi explained, which left it to the family to determine how much they wanted to know about the body: “On the first call from the medical examiner, the only thing they would say is, ‘I wanted to inform you that we have identified your son.’ Period. Then it’s up to you to say, ‘I’ll have the funeral director come in and pick up my son. Thank you. And don’t notify me until all the work is done’ or ‘Don’t notify me anymore. Period. No more. I’m bringing my son home and that’s it.’ Or you have the option to ask the medical examiner, ‘What did you find?’ That’s a very difficult decision to make.”

After all, Ielpi continued, the medical examiner could reply, “We’ve identified your son’s heart, just the heart.”

Such difficult moments prompt many questions, Ielpi added: “Then you also have to think about who found that heart. Who picked it up? Who held in his hand? Who put it in a red bag and tagged it?”

Ielpi reflected on the lasting impact of these searches: “These men and women that worked every day, and it wasn’t just firefighters and cops, it was the volunteers, the engineers, laborers who were finding these remains. And they live with that. I’m not going to get too explicit, but anything you can think of on your body right now, anything, and anything I can think of from my toes to the top of my head and in between, we found, and this went on for nine months.”

Ielpi knew of one family who wanted to be notified every time a body part was found: “I don’t know how many times they were notified, but it was many, many, many, many times that they got called from the medical examiner.”

Recovery with respect

It’s difficult for most – first responders and civilians alike – to imagine what it would be like to work amid body parts strewn across such a massive crime scene. But it’s what the rescuers and volunteers did, day after day, to honor the dead – always with respect.

One night in particular, Ielpi felt a sense of discomfort, not being at the site: “I had gone home early, and whatever it was, I just was angry, I think, and I just said, ‘Bullshit. I’m going back to the site.’ Where am I going to go? I don’t know where I’m going to go.”

It didn’t matter. Something had pulled him back.

After weaving around the site a bit, Ielpi saw a chief who could tell he was looking for a way to help, so he recommended that he join up with a particular crew.

“I could smell it already,” Ielpi said. “The smell of death is one of those horrible, horrible, horrible odors, but it also works out to your benefit because if you follow the scent, you may wind up finding the person.”

About 15 of them began seeking out the source, and they soon found it – a girl or woman; they were unsure of her age. She was tangled in rebar, hanging upside-down, a lot of bodily fluids present. They had to get her out for her family.

While crews were cutting the rebar, someone brought over a body bag. It was getting close; with one or two more cuts, she was going to fall.

“I said to myself – I wasn’t going to say anything to anybody else – ‘I’m not going to let her just fall,’” Ielpi remembered. “So I’m holding her, what there is of her, and the chief yells over, ‘Hey, Lee, don’t try to get her,’” fearing a messy, disturbing situation for Ielpi ahead.

Ielpi ignored the counsel. Another firefighter quickly understood Ielpi’s intent: “There was one other guy, I don’t know who the guy was, still to this day, and he said, ‘I’ll help you. I’ll hold her, too,’ and I just looked at him and gave him a smile.”

Crews cut the last one or two rebars, and the two men carefully maneuvered her into the body bag.

“Maybe she was saying thank you for not letting me fall,” Ielpi considered. “I don’t know.”

Badge #12642

Even with all the difficult memories of searching the site for his son, and others, Ielpi can still reflect on the positive role the fire department played in his life.

“The children knew nothing other than the fire service,” he said. “The volunteer service kept me very busy. I was a volunteer fireman for 38 years in Great Neck and went up the ranks, chief of department, and becoming a trustee in the department. Early on, I had a chief’s car, so the kids would be in the chief’s car with me. It was always exciting for them. They didn’t know anything else about their daddy except he was a fireman.”

The boys, years later, would follow in their father’s footsteps, first Jonathan, then Brendan.

And today, Brendan carries on the family tradition, Ielpi said: “My badge number, of course, went to Jonathan, and then because Jonathan was murdered, then the badge went to Brendan. 12642.”

‘We’re going to talk about tomorrow’

As if it weren’t far-stretching enough, Ielpi’s legacy goes beyond family and the FDNY. Just as his project to distribute World Trade Center steel around the world focuses on honor and education, so too does the 9/11 Tribute Museum Ielpi cofounded with Jennifer Adams-Webb in 2006, then named the 9/11 Tribute Center.

The museum is a project of the September 11th Families’ Association, a not-for-profit organization created by the victims’ families shortly after the attacks. The museum presents videos, artifacts and “Person to Person History,” linking visitors who want to understand the historic events of 9/11 with those who experienced them – from guided tours by family members, survivors and first responders to visual narratives told throughout the exhibits.

“The Tribute Center is a place for family,” Ielpi underscored. “Tribute is a place for the first responders, the volunteers that came to help and work, the people who lived and worked in the area. So, our docents, our guides – and we trained over 900 of them – were able to give tours and tell their story, real-life stories, and Tribute itself, again, it was built to reflect just that.”

Ielpi is one of those voices sharing his 9/11 story. There’s one room he does not enter, though – the room where his son’s turnouts are on display.

For those who have not been to the museum, Ielpi explained that, like the difficult stories he shared about his recovery efforts, learning about 9/11 is not easy: “You go through, and it’s going to be difficult. It’s going to be very difficult. In the last room, there were photographs. There were hundreds and hundreds of photographs – pictures of the dead. The families gave them to us. That was a very difficult room.”

But like Ielpi himself, who has found light amid darkness, there’s more: “Then you go downstairs and you smile, because we’re going to make you smile. We’re going to talk about tomorrow. We’re going to talk about how we cannot let this get you down – and that’s how Tribute ran. It’s the same way today.”

Learn more about the 9/11 Tribute Museum and Lee Ielpi.