This is the first in a four-part video series on command post management, detailing the acronym LABOR: Location, Announce, Box, Observe and Relax. Watch Part 2, which focuses on command post location, and Part 3, which focuses on Announce, Box and Observe. Part 4 will cover Relax and detail a mayday checklist for mitigating emergencies on scene.

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a four-part video series on command post management, detailing the acronym LABOR: Location, Announce, Box, Observe and Relax. Watch Part 2, which focuses on command post location, and Part 3, which focuses on Announce, Box and Observe. Part 4 covers Relax and details a mayday checklist for mitigating emergencies on scene.

By Marc Bashoor

No matter how many bugles you have on your collar, whether you wear a uniform or use a command chart, or even how calm you are, none of those things in and of themselves makes you a good incident commander. Your challenge is to take all of your training and experience and bring them together in an effort to bring calm to chaos.

Training and repetition will build the experience you need to feel better, calmer in the incident commander role. Does your department provide guidance, training and opportunities for you to practice?

With or without a robust training program, I encourage you to drill and practice on your own. Observe those who have mastered it and find your niche.

Part of bringing that calm to the chaos is understanding that you can’t be all things to all people. The beauty of the incident command system is the ability to bring geographic labor task management to the game so that you can take smaller bites of an incident and spread that division of labor around.

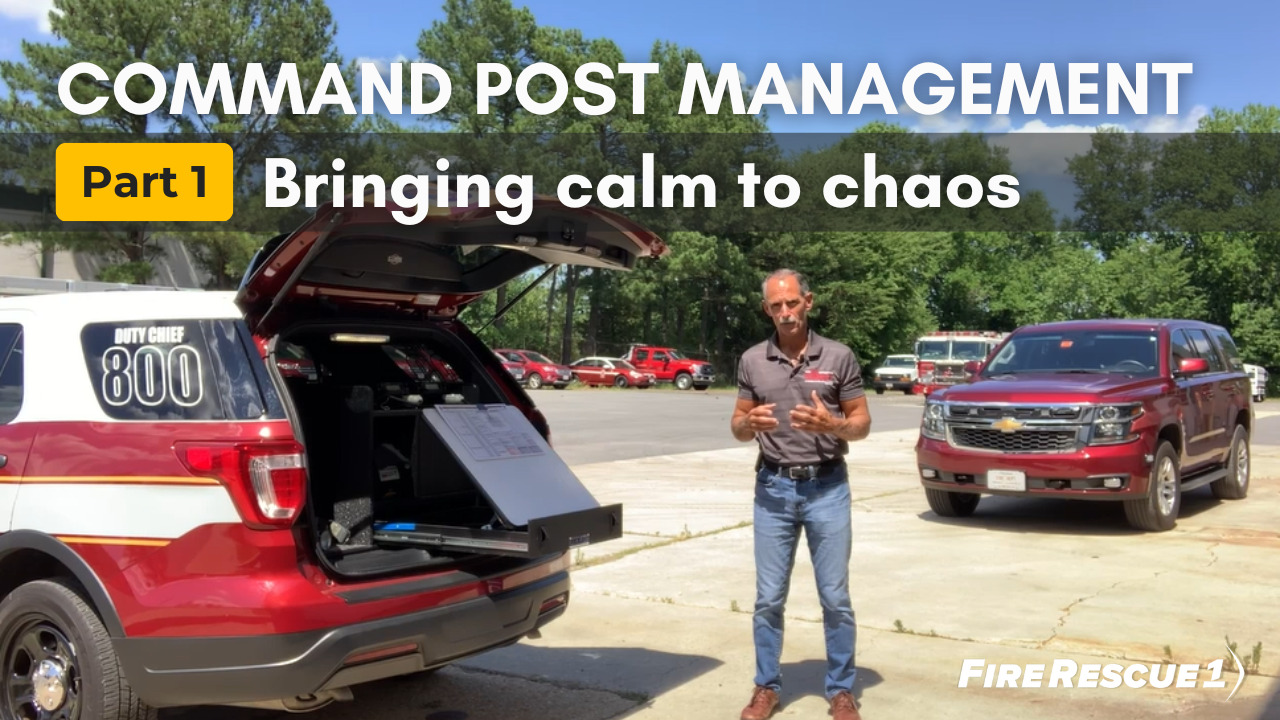

The command post – whether it’s at the back of a buggy, inside a buggy or at a fence post out front –really is the heartbeat of the incident, so I encourage incident commanders, especially new folks, to use this acronym to help understand the important parts of running that effective command post: LABOR

L – Location: You want to locate the command post in a place that is visible and that you have visibility at. Not only do you want to be able to see the incident and see where it’s going and be able to adjust one way or the other as needed, but you also need incoming people to be able to see you and to understand where that command post is so that they can report there to get their assignment.

A – Announce: We’re talking about announcing the location of your command post, the name of the command post, if that’s part of your SOGs, giving a brief CAN (conditions actions needs) report so that everybody that’s coming, and the dispatch center, understand what’s going on.

B – Box: Find yourself that 10 by 10 box and don’t leave there. The box might be this imaginary space behind a vehicle that’s set up for command or it might be the vehicle itself. The back of the vehicle is my preference. It might only be one person, but have a command support team – the only people you allow in that box; everybody else needs to deal with somebody else that’s outside of that box.

O – Observe: Part of being an effective incident commander is not just watching the fire but it’s observing everything going on, whether it’s listening for those telltale signs. It could be that mayday that you hear on the radio, somebody screaming, the sounds of a structural collapse, a pass device, screeching brakes coming at you from a different direction if you’re out on the highway. There’s any number of things that that incident commander needs to be observing.

R – Relax: Remember, this isn’t your emergency. You will not bring calm to the chaos by bringing chaos to the chaos. Chaos should never mean “chief has arrived on scene.”

So there you have it – LABOR: If you can master those things, you’ll begin to be able to have effective command post management – and you will begin to practice the art of bringing calm to chaos.

Whether it’s a fire or medical call, a mass casualty incident a hazardous materials incident, running that scene effectively with everybody going home safe, that’s what will make you an effective incident commander.

For more information on preparing new officers to be incident commanders, visit our special coverage series “Are you ready to run the show?” featuring a variety of useful articles and videos:

- The do’s and don’ts of commanding your first fire

- Managing multiple crews: Knowing how to prioritize and deploy resources

- Essential radio skills for new ICs

- Managing the risk of ‘move-up’ assignments in fire departments

- Reality Training: Tips for setting up incident command

- Policy points: 3 essential elements for incident command policies and procedures

- Q&A: Coaching is critical in training new ICs

- Code 3 Podcast: How to develop command presence

- How to deliver a strong 360-degree size-up

- Tips for ICs managing high-risk/low-frequency incidents