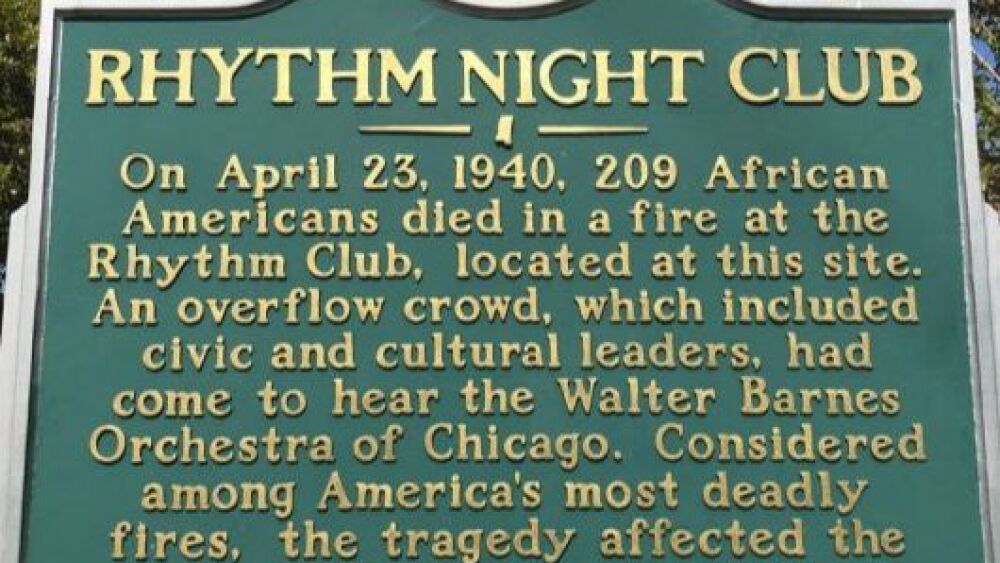

More than 80 years later, an almost-forgotten fire in Natchez, Mississippi, still ranks among the deadliest nightclub fires in history.

The building where 207 people died on April 23, 1940, was a dance hall called the Rhythm Club. It was a social gathering place for the African-American community of Natchez.

The source of ignition is thought to be a carelessly discarded cigarette. The contributing factors that led to such a tragic outcome included combustible decorations, overcrowding and an inadequate number of exits.

Failure to learn the lessons

By 1940, the U.S. had experienced enough fatal fires in theaters, clubs and restaurants to have learned some things.

One was the 1929 Study Club fire in Detroit, where 22 people died in the Prohibition-era speakeasy. It is thought that an improperly discarded cigarette was the source. Eleven years later, the Rhythm Club burned, followed by the 1942 Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston that killed 492 people. All three fires are notable for the contributing factors of combustible decorations and inadequate exits.

Fire behavior knowledge and fire ratings

It is not that we lacked an understanding of fire in buildings at that time; we actually knew quite a bit. In the 1920s, the National Board of Fire Underwriters, Underwriters Laboratories, the Factory Mutual insurance companies and the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST) joined forces, led by Simon Ingberg, to conduct fire tests of buildings and materials. The results were published in 1928 under the title “Tests of the Severity of Building Fires.”

With the help of the Washington, D.C., Fire Department, the research team set fire to former federal office buildings. These real-world fires were evaluated, and the standard time-temperature curve was developed to quantify the destruction of buildings under a standardized fire exposure test. From these tests came the concept of fire-resistance ratings.

Although we call the Rhythm Club a dance hall, from a fire protection standpoint, it is a place of assembly. We classify uses (how a building is used or occupied) for the purpose of applying the model building codes. Classifying by use makes sense from a regulatory point of view because it directs our focus to floor area, number of people present (both sitting and standing) and the reason why they are gathering. Are they dancing? Are they drinking? Are they watching a movie or a play?

Knowing who will occupy the building and their anticipated activity serves to determine the essential safety features required, especially the means of egress, defined as an unobstructed path to leave occupied spaces. Further, means of egress consists of three distinct parts: exit access, exit and exit discharge. The availability and adequacy of the means of egress stands as the most critical life safety feature.

Facts about the fire

Here are some basic facts about the Rhythm Club fire to consider as we face new fire and life safety threats in our communities.

The building:

- It was located at 5 Saint Catherine St. in Natchez, Mississippi.

- The 4,560-square-foot building was originally an auto repair garage.

- The single-story, wood-framed building was covered with corrugated metal sheets.

- Of the 24 windows, 21 were shuttered and nailed shut, two had iron bars, and one was open.

- The single 38-inch entry/exit door on the front side opened inward.

- A second door on the front side was padlocked.

- The main entryway foyer led to the lobby through two 36-inch inward-opening doors.

- From the lobby a single 36-inch door led to the dance floor.

- A hamburger grill was located near that door.

- It is thought that a cigarette discarded near the grill started the fire.

- The lobby led to the dance floor, which took up the majority of the floor area.

- A stage for the band was at the far end of the dance floor, opposite the entrance.

- Adjacent to the small stage was a bar serving alcohol.

- The interior was decorated with dried (and very combustible) Spanish moss suspended from wires attached to overhead exposed joists.

- The Spanish moss had been treated with kerosene to repel insects.

- The interior walls were covered with wood shiplap boards to 5 feet above floor level.

- The dance floor was constructed of wood planks over poured concrete.

The event:

- Tickets were sold out for popular Vicksburg, Mississippi, native Walter Barnes and his Chicago band, the Royal Creolians.

- An estimated 700 people were in attendance.

- Shortly after 11 p.m., a fire started near the hamburger grill.

- The Spanish moss ignited, spreading fire rapidly over the heads of patrons.

- The single door between the dance floor and the lobby became a choke point.

- Those beyond the lobby area were trapped by fire as pieces of burning moss fell, igniting their clothing.

- The fire forced those who remained deeper inside toward the band platform.

- The most deaths occurred in this area.

- Seeing fire and a panicking crowd, Barnes asked for calm and told his band to play.

- Walter Barnes and nine band members died when the roof collapsed on the stage.

The fire department response

The 13 volunteer fire companies of Natchez had a history dating back 100 years. Two of the companies had paid drivers.

The first call came in around 11:15 p.m., and paid drivers Richard Walcott and William Druetter started the response.

The first engine took a hydrant a block west of the club and laid in with a 2½-inch supply line and commenced an attack with two hose streams. One stream was directed into the front entrance and trained upward into the ceiling space. The second line was directed through a side window into the open area of the dance hall where the fire burned overhead. The heaviest fire was quickly knocked down.

Druetter (later made chief of department) was at the front of the structure and later recalled: “The fire was a seething mass of flames, making it impossible for anyone to enter or exit the front of the building. … No one came out of the building on their own.”

Without the benefit of breathing apparatus, several firefighters attempted entry to search for victims. One firefighter crawled out to report that he could not pull anyone out because he believed he had run into a pile of tangled bodies.

The water from hose streams striking the corrugated metal siding produced steam, aiding suppression efforts. The steam likely caused further injury to any victims still alive inside or killed them outright.

Ambulances arrived to transport burn victims to the hospitals. Medical help from the community responded to the nightclub and nearby hospitals. Despite segregation, the white medical community saw no boundaries, only people needing help.

The aftermath

As one might expect following a horrific tragedy, fire protection and prevention efforts were emphasized in Natchez. The sight of posted occupancy signs became the new norm, a permanent fixture in places of public assembly. Panic bar hardware on exit doors came into widespread use. The city began the transition toward a paid fire department with a full-time chief and fire inspector, jointly responsible for adoption and enforcement of fire prevention codes.

Among the victims were some of the city’s prominent young African-Americans. Many victims, burned beyond recognition, could not be identified. They were buried in a mass grave outside town. Today, a few people try to remember the lost lives and honor them by preventing the grass and weeds from overgrowing the spot.