By Bruce Hensler

The Yarnell Hill Fire is the third deadliest incident for wildland firefighters, one of more than a dozen line-of-duty death incidents since the 1910 Devil’s Broom Fire in which 78 firefighters were killed during suppression efforts in Washington, Montana and Idaho. Some incidents are forgotten, such as the 1938 Pepper Hill Fire in Pennsylvania where eight firefighters died – a supervisor and seven teenagers. These young men of the Civilian Conservation Corps had minimal firefighting training. It was their second fire, their first being the day before. There were lessons learned that should have served future firefighters, including those who died at Mann Gulch, Inaja, South Canyon and Yarnell Hill. But as history shows, we routinely fail to learn those lessons.

Yarnell Hill: the human factor

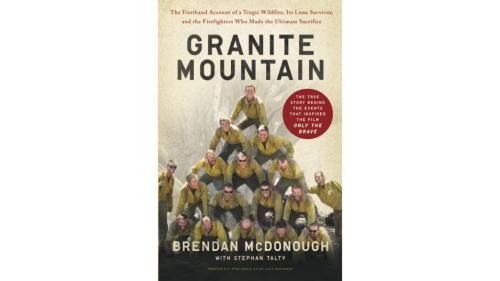

In “19: The True Story of the Yarnell Hill Fire” (Outside Online, 2013), Kyle Dickman introduces the 19 Granite Mountain Interagency Hotshots (GMIH) who died during the fire near Yarnell, Arizona. His narrative reveals the 19 as individuals with heart and soul and a desire to fight wildfires. That is in contrast to official reports that reveal little of the hotshots as people. This is not unusual for investigative reports by agencies with oversight.

While investigation reports tend to distill incident details down to the facts and figures, it is the more elusive human factor that is perhaps most telling when trying to understand decision-making – and determine lessons learned.

Hotshow crew deployment

We know the Arizona Forestry Division requested Southwest Coordinating Center (SWCC) in Albuquerque to provide a hotshot crew. Dispatchers at SWCC checked the list of available hotshot crews. “Available” meant rested and ready, and because the Granite Mountain crew was coming off of a hard 13-day stretch, SWCC dispatched the Blue Ridge Hotshots.

Despite that assignment, dispatcher logs reveal an unusual email sent directly to GMIH boss, Eric Marsh, requesting his crew the next morning. Marsh accepted despite his crew having worked extensively over the previous 30 days. The record is unclear as to whether he was aware that Blue Ridge had been summoned. In a Los Angeles Times interview, noted fire historian Stephen Pyne said, “They self-deployed on an email. No one does that. No one.” (In the federal government system, official orders for deployment are required for tracking and financial accountability purposes.)

Granite Mountain was the nation’s only municipally funded hotshot crew; for them saving homes was important. That too is significant because their home base was the city of Prescott, located in a wildland-urban interface area by a national forest.

Marsh was by all accounts highly qualified, respected, well-liked and notably driven. The area incident commanders were experienced. Yet the firefight is one of missed opportunities, bungled communications, and the sheer power of nature.

It is still unknown why the crew left a relatively safe area. Some think that they may have been trying to get closer to the vulnerable houses. Marsh’s motto was adopted by the GMIH: Esse Quam Videri, which translates as “to be, rather than to seem.” Marsh was mission-driven.

No verified communications exist to inform us as to decisions made prior to entrapment.

The psychology of decision-making

Despite all the lessons shared after other LODD incidents, we often fail at learning them. Are the lessons too difficult to digest because they require behavioral change? Fires with LODDs are most likely to result in tangible change, like developing rules of engagement. But safety rules are notorious for opening the door to blame-shifting.

The families of deceased firefighters see engagement rules, like the 10 Standard Fire Orders, in the same light as do many firefighters, as an avenue to blame the fallen. Efforts to translate lessons learned into something tangible often result in more layers of confusion, adding rules, acronyms and catchphrases.

Dr. Ted Putnam, a psychologist with extensive wildland firefighting and investigation experience challenged the 10 Standard Orders in a 2001 paper titled, “Fire Safety: Up in Smoke?” His goal was to expose the truth about the real causes of wildland firefighter fatalities, injuries and near misses. His motivation was his own silence as well as that of other investigators in the face of cover-ups of deadly fires by managers and administrators.

In Putnam’s view, the 10 Standard Orders equate to a zero-risk mentality, thus implying that if you want to be safe, then stay home. Putnam presents six statements for consideration:

- There is a lack of fire management support for human factors

- Safety is not No. 1

- No one can follow the 10 Standard Orders

- Most wildland fire entrapment investigations involve covering up evidence

- Active concern for safety is punished

- We are a long way from becoming a learning organization.

Read Putnam’s essay and think about Yarnell Hill.

Norman Maclean, author of “Young Men and Fire” conducted extensive research on the 1949 Mann Gulch Fire. Karl Weick, an organizational psychologist, subsequently built upon Maclean’s extensive work to develop a theory for organizational development.

Both men held that the lessons of Mann Gulch are critical to developing an understanding of organizations, specifically why they unravel at critical times and how they might be made more resilient. The theory is presented in “The Collapse of Sensemaking in Organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster” (Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 38, pp.628-652).

Looking beyond mistakes, Maclean and Weick sought tangible lessons. Maclean saw Mann Gulch as a race away from fire toward life while running uphill in rough terrain. Twelve of the 15 smokejumpers and a forest ranger lost the race.

Weick sees the Mann Gulch Fire as involving “… the interactive disintegration of role structure and sensemaking in a minimal organization.” In less academic terms, the violent eruption of fire at Mann Gulch overwhelmed the expectation of the smokejumpers that they were fighting a “10 o’clock fire” (an “average fire,” in smokejumper terms).

As a freight train of fire bore down on them, their sense of things was disrupted and as if that wasn’t enough, what their foreman did must have blown their minds. He ordered them to drop their tools and proceeded to light a fire in front of them, ordering them to lie down in the burned area. His idea was that tools impeded their escape and that starting a fire would clear a small burned spot for them while the larger fire blew over. Unfortunately, he was ignored, but he survived by his improvising. Two smokejumpers made it to the ridge, slipping through a crevice to escape, thus, only three survived.

Weick’s thesis is that the act of fleeing (firefighters running from fire), abandonment of tools (loss of self-image) and their foreman igniting a fire (what is he doing?) affected their thought process. None of the smokejumpers were acquainted with each other or their foreman. This lack of familiarity limited any cohesion they might have had.

Weick contends that organizational resilience in the face of high-risk activities improves when leaders develop groups capable of four things: 1) improvisation, 2) wisdom, 3) respectful interaction and 4) communication – all nonexistent at Mann Gulch.

That wasn’t the case at Yarnell Hill. Eric Marsh and the Granite Mountain Hotshots were a cohesive and supportive group. However, was Marsh too respected or members too trusting at the critical moment to question his leadership? We don’t know, but we might rely here on Putnam, who questioned the 10 Standing Orders.

Putnam believes wildland firefighters will continue to die as long as they fail to acknowledge and come to terms with certain realities by acknowledging the trap of a can-do spirit; unwise agency cost-control measures; image of self, crew and agency; and the recurring failure to learn from lessons.

This article, originally published on June 27, 2019, has been updated.