Imagine: A devastating 7.9-magnitude earthquake has just struck your city. Your fire chief has been fatally wounded in a building collapse. Several fires have ignited as a result of the damage, culminating in a conflagration that gradually consumes everything in its path. The year is 1906, the streets are filled with debris, and your fire engines are hauled on carriages by horses.

And, you have no water.

This was the nightmarish scenario faced by firefighters in San Franciso after the Great Earthquake struck the city in the early morning hours of April 18. 1906.

A firsthand account, written in the months following the quake by Chief Engineer Patrick H. Shaughnessy and archived by the Museum of the City of San Francisco, summarizing the desperate situation after the earthquake broke through most of the city’s water mains.

“In the vicinity of every fire house buildings were being consumed by the flames and every effort was made to extinguish the fires. Hydrant after hydrant was tested and not a drop of water was to be found,” Shaughnessy wrote. “Our system was paralyzed and we were practically helpless.”

But even as their city crumbled and burned around them, firefighters did not lose their determination. And amidst the devastation, a ray of hope – or what some would call a miracle – appeared just as the conflagration threatened to wipe out the historic Mission District.

A lone hydrant, somehow still functioning despite all odds, supplied firefighters with enough water to extinguish the flames and save the Mission District from certain annihilation. More than a century later, the so-called “little giant,” or “golden hydrant,” remains a local legend, as well as a reminder of how San Francisco transformed its water supply system to ensure the city would never again need to rely on a miracle.

The great earthquake and the tale of the ‘little giant’

To this day, the Great Earthquake of 1906 is known as one of the most destructive and deadliest earthquakes in U.S. history. In total, about 28,000 buildings were destroyed in the quake and subsequent fires, and more than 3,000 people were killed, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Among the fatalities was San Francisco Fire Chief Dennis T. Sullivan, who died four days after being gravely injured when the quake caused a neighboring building to collapse on his firehouse residence.

Archives of firefighters’ reports published by the Museum of the City of San Francisco show how engine companies scoured the city for water to quell the dozens of blazes that ignited for several days after the quake. Time after time, firefighters found hydrants unusable, or with barely enough pressure to produce a stream. Cisterns throughout the city meant to provide an extra emergency water supply were also not spared by the earthquake, as many were already decades old and had not been properly maintained.

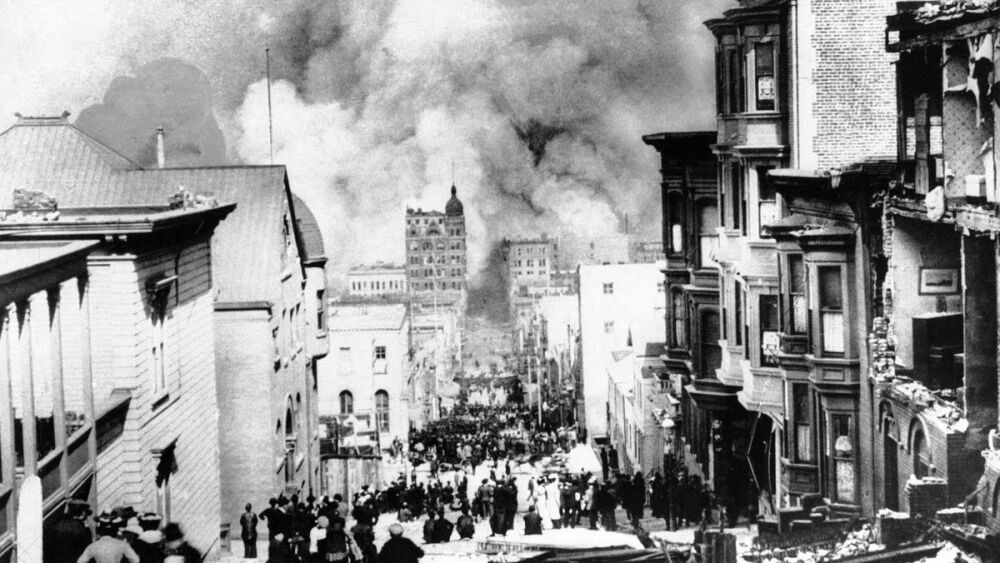

Massives fires in the aftermath of the Great Earthquake of 1906 destroyed thousands of buildings and threatened to turn the entire city of San Francisco into a pile of ash. Firefighting efforts were hampered both by debris leftover from the quake and by the destruction of water mains and cisterns firefighters relied on for water supply.

AP Photo/Arnold Genthe

Still, firefighters did what they could, getting whatever they could from leaking cisterns, trying each and every hydrant and pumping seawater in their efforts to control the growing conflagration. As flames spread into the Mission District, firefighters desperately searched for a water source but found that every hydrant in the area was inoperable.

As the story is retold in a 2010 article in the San Francisco Examiner, one of the many residents who had fled up to what is now Dolores Park discovered the “magic hydrant” at the corner of Church and 20th streets. Firefighters rushed to get their engines to the one working hydrant, but their horses were too exhausted to climb up the hill to reach it. So, several residents helped firefighters hook ropes onto the engines and pull them up to the corner, where the hydrant stood as the sole lifeline against the growing blaze.

Contemporaneous reports from fire officers at the scene recount the effort from there:

“By connecting with several engines a line was extended from Twentieth and Church St. to Mission St., and a strong stream was obtained,” wrote Capt. James Radford of Engine Co. No. 25. “Another line was led from a cistern on 19th St. near Shotwell St., and with the aid of these two streams the fire was extinguished at this point on April 20th, at about six a.m. This Company was on duty for fifty-five hours.”

Capt. Arthur Welch, of Engine Co. No. 7, reported: “In connections with Engine No. 27 and 19 we had sufficient hose to fight the fire down the north side of 20th St. to Mission St., where the fire was extinguished on the morning of April 20th ... due to the fact that we were able to obtain a supply of water we were able to stop the fire from crossing 20th St., and destroying the complete Mission district.”

According to the Guardians of the City, the historical branch of the San Francisco Fire Department, Police Department, Sheriff’s Office and EMS agency, the firefight was also aided by “volunteers with buckets and wet sacks.”

On the morning of the second day after the Great Earthquake, although much of the city was in ruins, the Mission District was saved through the tireless work of firefighters and the miracle hydrant that came to be known as the “little giant” of San Francisco.

A turning point for disaster preparedness

The catastrophic failure of the city’s water supply system in the wake of the disaster spurred city leaders to study why the failure occurred, and implement solutions that would ensure the city was protected in the event of another earthquake.

San Francisco City and County officials wrote in the Municipal Record in 1925 of the efforts taken to build a new reliable water system. A study conducted on fault lines in the region found that any pipe system would cross over those lines, risking the breakage of water mains during a future quake. It was also found that the city’s 54 cisterns, built back as far as 1860, were in disrepair and lacking reinforcement to withstand the force of a quake. These results led engineers and officials to determine that a new auxiliary water system, completely independent from the rest of the city’s water supply, would be needed to ensure firefighting readiness should all else fail in a disaster.

Although he was killed before these decisions were made, Chief Sullivan can be credited for much of the changes made to improve the water supply, Guardians of the City Trustee David Ebarle told FireRescue1.

“He had been advocating for a secondary or what became known as the Auxiliary Water Supply System (AWSS) prior to the quake,” said Ebarle, who is also the lead EMS agency specialist of special projects at the San Francisco Department of Public Health. “As with many governmental projects, it was not pursued until after the great quake.”

Contemporaneous reports show that even on his death bed, Sullivan was calling for further safeguards against extreme fires.

“After recovering consciousness the chief took great interest in the affairs of the city, being always apprehensive that a fire would break out,” read the article in the Los Angeles Herald announcing the chief’s death on April 22, 1906. “He knew from the first that he would die from his injuries, but never forgot the interests of his department. His mind seemed to dwell on the need by the city of a salt water fire fighting plant, and he repeatedly spoke to his friends of the increasing necessity for such an adjunct to the fire department of the city.”

As it would come to be, saltwater pumping stations would become a part of the Auxiliary Water Supply System, a $6 million project approved by San Francisco voters in 1908. Adjusted for inflation, that amount would equal more than $174 million today.

The Auxiliary Water Supply System consists of multiple fail-safes to ensure water is available to firefighters even if the rest of the city’s water system fails. The high-pressure system includes a reservoir and two tanks elevated high above the city to allow water delivery by gravity, according to SFFD. These elevated water sources can hold more than 10 million gallons of fresh water and are regularly serviced and maintained by the San Franciso Bureau of Engineering and Water Supply.

High-pressure pipelines in the city are also divided into three zones and incorporate gate valves at frequent intervals to allow a damaged section of pipe to be isolated from the rest of the system. This ensures the rest of the system remains functioning even if one section breaks.

The city’s underground cistern system was improved and expanded after the Great Earthquake, and now consists of more than 170 cisterns holding a total of about 11 million gallons of water. The cisterns are completely separate from the rest of the city’s water supply, and from the rest of the high-pressure system, offering additional backup even if another component of the water system is damaged.

The newly-built cisterns were reinforced to better withstand the force of an earthquake, and when the 6.9-magnitude Loma Prieta earthquake struck in 1989, only one of the cisterns leaked while the rest remained undamaged, according to Atlas Obscura. The cisterns are regularly inspected by the SFFD and kept full by the Bureau of Engineering and Water Supply.

The auxiliary system underwent an additional $102.4 million construction project beginning in 2013, which strengthened the reservoir, tanks and saltwater pumping stations against seismic activity, repaired cisterns and added additional cisterns, and made repairs to the more than 135 miles of pipelines and tunnels running underneath the city.

Now, 115 years after a lone hydrant aided the historic battle against a massive blaze, 1889 high-pressure hydrants stand at the ready to prevent another fiery nightmare.

The golden legacy of the little hydrant that could

In the decades since the Great Earthquake, as new cisterns and hydrants were constructed across the city, the miracle hydrant continued to sit at the corner of 20th and Church, receiving little attention for many years. According to the Ebarle and the San Francisco Examiner, it wasn’t until the late 1960s that a local dentist and historian named Doc Bullock decided to highlight the “little giant” by painting it gold.

This “gilding” of the hydrant sparked a tradition that has since carried on for decades, most recently on the 115th anniversary of the quake in 2021. Every year on April 18, fire department members and relatives of earthquake survivors gather in the early morning hours, first stopping at Lotta’s Fountain, another landmark that survived the quake.

After a commemoration ceremony at the fountain, a procession then makes its way toward Dolores Park, where the miracle hydrant is painted gold at 5:12 a.m., the exact time the Great Earthquake struck San Francisco. This yearly tradition earned the hydrant its second nickname of the “golden hydrant,” which shines as an example of firefighters’ and San Franciscans’ resiliency, and a reminder of the lessons learns and changes made to improve preparedness.

A plaque at the site of the hydrant, donated by the Upper Noe Valley Neighborhood Council, was dedicated in 1966 to “Chief Dennis Sullivan and the men who fought the Great Fire and to the spirit of the people of San Francisco.”

The plaque’s dedication continues: “May their love and devotion for this city be an inspiration for all to follow and their motto, ‘The city that knows how,’ a light to lead all future generations.”

San Francisco's Fireboat Station 35 features modern design connected to historic charm

The floating fire station has drawn curious eyes from around the world, starting with its initial conception and extending to crew operations

This article, originally published in May 2021, has been updated.