By Stephen Tuck, FireRescue1 Contributor

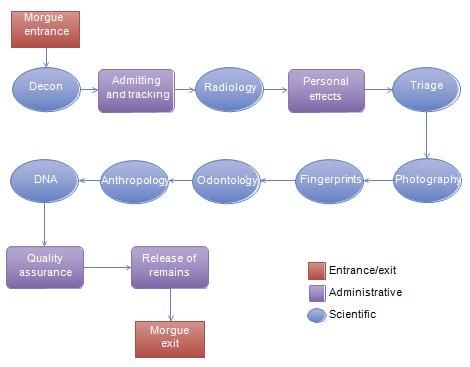

Road rescue operators are trained to address an astonishing range of road crash situations. Accidents where a car is on its roof are particularly challenging.

A technique known as “cracking the egg” may be suitable where a car has overturned and space is at a premium (e.g., the roof has collapsed).

It may also be useful if the front doors cannot be removed, or if a straight-line extrication is required (e.g., where it is likely the victim has a spinal injury), or if the victim is bariatric.

The first step is to remove the rear doors (for the purposes of this discussion it is assumed that the vehicle is a sedan and that rear seats are unoccupied).

Crush the door sill with the spreaders to create enough space to insert the spreader tips (see Figure 1 below).

Crushing the door sill. (Photos/Stephen Tuck)

The base of the door should be strong enough to take the pressure required to break the door latch. If you run into difficulties, work the spreaders around the door from the base to the latch to break it. Once the latch is broken and the door opened, it can be removed entirely by unscrewing or by spreading and breaking the hinges.

Once both rear doors have been removed, make a relief cut through the door sill a few inches rearwards of the B-pillar. Remember to remove the interior trim first to check for any hazards (see Figure 2 below). While this is happening, another crew member should be tasked with removing or neutralizing dangers from any fuel lines, exhaust pipes or other under-vehicle fittings.

Relief cut in door sill.

The spreaders should now be equipped with chain-tips and opened to their fullest extent. Chains should be run in a Y-pattern from each speader tip to the front and rear crossmembers. It may be helpful to rest the spreaders on some stabilization blocks (see Figure 3 below).

Placement of chains and spreaders.

Two ratchet straps should be run from the rear to the front of the vehicle, with the ratchets hooked on at the front. The crewmember tasked with this job should take care to hook the straps and ratchets securely (towing points and crossmembers may be suitable). The straps should be left free in the ratchet and not tightened, and a crewmember assigned to each ratchet.

By this point, the rescue team is ready to crack the egg by lifting the entire rear of the vehicle. Use the shears to cut the C-pillar near the roof (before cutting, consider whether this will cause the body of the vehicle to move and whether stabilization is required). The spreader operator should then close the spreaders in a single non-jerky movement (see Figure 4 below).

Rescue team preparing to “crack the egg.”

This will raise the back of the car and allow access to the victims in the front seats (see Figure 5 below). At the same time, as the rear of the car is lifted, the ratchet straps should be quickly pulled through the ratchet which is then engaged to tighten the straps (see Figure 6 below). This is a safety measure to hold the load if the spreader or chains somehow fail.

Access has been gained to the victims.

Be careful not to pull the rear of the car past its tipping point. Unless the rescue team has set up a winch and is ready to do a controlled lowering, the falling section will cause a lot of movement in the vehicle and risk further injuring the victims or trapping a crewmember. Because there is always the risk of the spreader operator accidentally tipping the lifted section, cribbing blocks should be placed on the floor pan to reduce the risk of a hand or arm being trapped.

Note use of the ratchet straps to ensure safety for crew and victims.

This technique should not be used often: as noted, it carries inherent risks of vehicle movement and hazards for both responders and victims. It is also reasonably involved and may cause the extrication to take longer than the 20 minute ideal. [1] However, in some circumstances, it will enable rescuers to create enough space to extricate a victim safely.

References

1. Dunbar I. Vehicle extrication techniques (n.p., Holmatro: n.d.);103-4.

About the author

Stephen Tuck is a road crash rescue volunteer and controller of the Tatura Unit of Victoria State Emergency Service, Australia.