In previous articles, we discussed how firefighters are exposed to a variety of fireground contaminants. We have even gone so far as to pinpoint the blame that many of these exposures primarily occur due to the lack of liquid-tight interfaces between the different parts of the protective ensemble.

Further, it is our opinion that the protective hood worn as an interface device is due for improvement. Our contention has been that the protective hood has the difficult function of having to create an interface with several ensemble parts that include the SCBA facepiece, the helmet and ear covers, and the coat collar.

Even when all these clothing item are properly deployed and worn as instructed by manufacturers, there are portions of the head and face that remain vulnerable due to the way that protective hoods have been institutionalized as part of the protective ensemble.

We further echo the outcry from many other organizations that there is an unacceptable increase in the rate of certain cancers striking down firefighters.

Exposure risks

While recent epidemiological studies appear to conclusively show that specific cancers occur at elevated rates as compared with the general population, there is a relatively difficult task to scientifically establish the cause link between fireground exposures at structural fires with the onset of specific chronic diseases including cancer.

Still, the International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified the occupation of firefighting as possibly carcinogenic and may change its findings to probably carcinogenic.

Exposure to cancer-causing agents likely occurs on the fireground as well as in the aftermath of firefighting activity, particularly if clothing is not cleaned. Firefighters lament that following a working structural fire, their work uniforms, under clothing, hair, and even their skin can continue to smell like smoke, sometimes even after repeated showers.

The fact is that fire smoke, which consists of minute particles, easily penetrates into the ensemble. And the problem is the unburned carbon that make up the bulk of those particles carry with them the toxic gases from the combustion process.

Particle infiltration study

While you can see the smoke, the particles are actually quite small — most have a diameter less than a fraction of a micron (approximately a hundred thousandth of an inch). It is no wonder how these particles get into your skin. Yet the moisture barrier layers used in garments, gloves, and footwear will prevent even particles of this size from infiltrating the clothing.

To show how firefighters can be contaminated by smoke, the International Association of Fire Fighters commissioned full ensemble particle exposure testing at Research Triangle Institute in early January. This evaluation involved a used turnout clothing system, configured with a SCBA and worn by a test subject in a particle-laden chamber.

The evaluation was performed per the Department of Defense based Fluorescent Aerosol Screening Test procedures where the individual was subjected to a high-level concentration of silica powder particles tagged with the fluorescent tracer having a particle size ranging from 0.1 to 10 microns. The test subject performed a variety of different movements over the course of a half hour while particles were blown through the chamber at 10 mph.

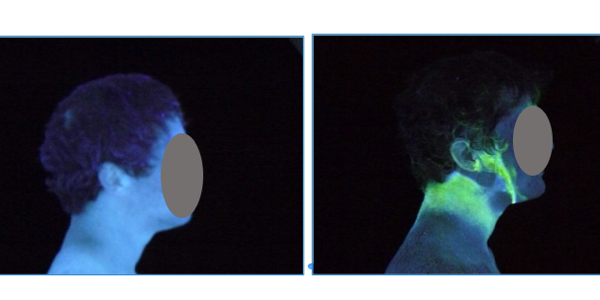

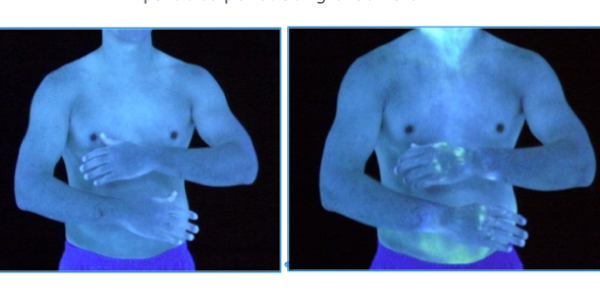

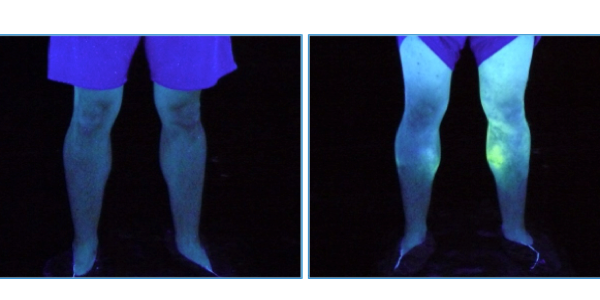

Following the exposure, the exterior of the garment was then wiped down and the ensemble carefully removed to avoid exterior particle transfer to the interior. Black light photography of the individual without the ensemble before the chamber exposure and after the exposure provided a means for detecting where inward leaking occurred.

The following pictures show the test and where the infiltration of particles was observed.

The results

These results are extremely significant because they confirm the suspicion that a large amount exposure occurs to the vulnerable face and neck area that is not protected by the SCBA facepiece. The photographs also show particles entering the garment through the front closure and between the coat and pant interface to less significant extent.

Low levels of particle penetration were also observed at the glove-to-sleeve interface. But relatively surprising was the intensity of contamination on the calves above the boot line despite the extensive overlap between the pants and boots.

What these pictures show is what we have always known to be true, but never really cared to admit — smoke easily penetrates clothing, primarily at interface areas, and serves as pathway for firefighter exposure on the fireground.

This evidence should compel the fire service to take a serious look at the way it practices hygiene following a fire. This includes performing gross decontamination of gear at the scene, taking a shower as soon as possible following a structural fire as well as changing gloves and subjecting the gear to full cleaning.

The pictures also tell a story that the fire service industry may want to rethink how it approaches interfaces by developing clothing systems that create the least encumbrance while still trying to achieve some attenuation of particle infiltration.

It is one thing to write and speak about firefighter exposures, but it is an entirely different matter when pictures can tell you a truth about exposure that cannot be ignored.