“Change is the only absolute.”

I would write that on the chalkboard when I taught graduate courses on organizational development in the 1990s.

Plato and Aristotle also taught change, specifically the philosophical aspects to the change construct – we need change and resist change, want and fear change, desire and condemn change. I am not sure what instructional technology Plato and Aristotle used in their classes.

As for me, my instructional teaching comes from a variety of sources. If you took any National Fire Academy (NFA) Executive Development, Organizational Development, or Management Science curriculum courses between 1980 and 2014, you most likely studied one or more of these six theories:

- Diffusion of Innovations by Everett Rogers

- Significant Emotional Events by Morris Massey

- Planning Assumptions by Douglas Eadie

- Paradigms by Joel Barker

- System of Profound Knowledge by W. Edward Deming

- Organizational Culture by Edgar Schein

These theories form the source material for what I call the “Clark Cultural Change Process Model.” Before we delve into each theory, let’s first look at how I process this information – and how you can, too.

‘The product is only as good as the process’

One of the skills I am supposedly good at is taking complex, disconnected ideas and making them easy to understand and connected in new ways. For as long as I can remember, I have tried to figure out the who, what, when, where, how and why of almost everything in my life in the cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains – even before those big words became part of my vocabulary.

You see, I am dyslexic, and dyslexic brains work differently. We process written language outside the normal method used to learn to read and write. We come to see ourselves different than others, and the world sees us different, too. For some unknown reason, I became sensitive to the process in which the answers to who, what, when, where, how and why were achieved. I came to understand that if the process changed, you got a different answer.

If you took one of my classes, you remember that I would say, “The product is only as good as the process.” Some of the class plaques I received from students even have that saying on them. The NFA curriculum was mostly about process because students from different fire departments would have different answers to the who, what, when, where, how and why to meet their organizational and individual needs.

This approach ultimately helped strengthen my personal process toward affecting fire service cultural change and the National Fire Academy being a leading driver of fire service culture change, particularly in the areas of firefighter safety, executive development, incident command, fire prevention, hazmat, arson investigation, community risk reduction, applied research.

The changing concept of ‘normal’

Fire service culture became my obsession after the first National Fallen Firefighter Summit in 2004. I was the facilitator of the group that created Firefighter Life Safety Initiative 1: Define and advocate the need for cultural change within the fire service related to safety, incorporating leadership, management, supervision, accountability and personal responsibility.

The study of the fire service needs to include culture in general because the fire service fits into the bigger human culture paradigm. After all, we put names and values on all change because it is human nature to do so. The physical world does not judge, it just changes; it is the humans who pass judgment on the change, even in the fire service.

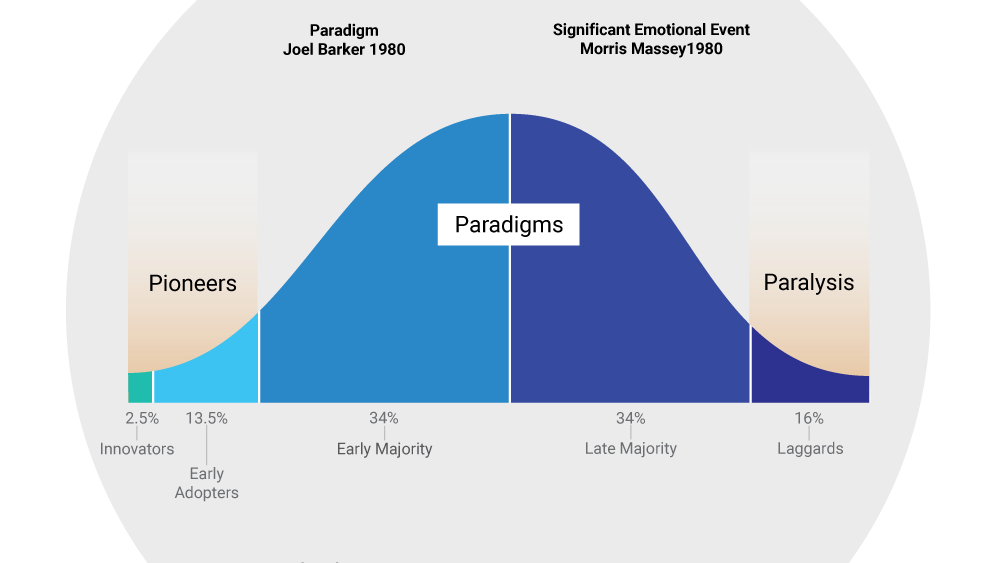

Today, everything that we think is “normal” (because the 68% of us in the middle of the bell curve agree) was at some previous time an outlier or not even thinkable. Remember, humans “knew” the earth was flat, the earth was the center of the universe, talking through a wire was magic, polio was the biggest fear of every parent, and woman could not be firemen/firefighters.

In 1970, when I began my fire service journey, only the chief had a portable radio, Nomex did not exist, there were no seat belts in fire trucks, we rode on the back step of the engine or side of the ladder truck, home smoke alarms didn’t exist, there was no “America Burning,” no National Fire Academy, no female firefighters, and the list goes on and on. The social, political, economic and technological changes in the fire service have been significant.

The rate, volume and novelty of change will only increase in the 21st century.

Spock wished us to “Live long and prosper.” Our ability to deal with change directly impacts how long we live and how well we prosper. This is true for individuals, groups, organizations and humanity.

6 theories of change applied to the fire service

As we evaluate change in the fire service, it’s useful to study the six theories used in the change model.

1. Rogers’ 1968 Diffusion of Innovation Model

There are four aspects to Rogers’ model:

- The innovation itself

- Communication channels

- Time

- A social system

Let’s apply Rogers’ model to the fire service using a personal example. It took 10 years after I wrote my first mayday-focused article in 2001 for the NFPA to change the standards to allow firefighters to use the word mayday, even though the word was in common use, including at the National Fire Academy, since 2005.

After the first NFA mayday online course was delivered (the innovation), the acting U.S. fire administrator was notified by a national fire service organization that firefighters were not allowed to use the word “mayday” because the NFPA standard stated that the term was only for ship and aircraft in danger (the start of communication channels). I was summoned to my supervisor’s office and told to stop using the word mayday. After listing to my supervisor, I handed him a letter that I had received in 2002 from the National Search and Rescue Committee, a federal group, noting it was OK for firefighters to use the term mayday, and it would not interfere with ships and aircraft. Finally, in 2012, the IAFF was able to get NFPA to change the standard and allow firefighters to use the term (a social system is developed over time; see PDF below).

2. Massey’s 1970 Significant Emotional Event (SEE)

There are three age periods:

- Imprint – birth to age 7: We learn right, wrong, good, bad, mostly from parents.

- Modeling – 8 to 13: We copy people around us – parents and others.

- Socialization – 13 to 21: We are influenced by our peers. We look for people like us in person and in the media.

Some of our strongest values are shaped early in our development but can be radically changed later in life if we experience a significant emotional event (SEE). An SEE can cause us to change our most concrete value. Brian Hunton was a National Fire Academy graduate. When he fell out of the fire truck and died, I felt responsible and have been trying to change the fire services seat belt culture ever since.

3. Eadie’s 1983 Planning Assumptions

The concept of Planning Assumptions was part of the NFA Organizational Analysis and Renewal (OAR) course. The objective was to help fire departments implement what they learned at the NFA.

The first step was for the leadership team to identify their assumptions about the future related to Social, Political, Economic and Technology factors and to monitor the continuing numeric accuracy of the assumption. If the assumption changes, the plan was changed. What most of us, the middle 68%, see as normal is dependent on our collective agreement on whether how things work today will be the same as how they will work tomorrow. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused all of us to realize our assumptions about tomorrow were not accurate – and our plans changed.

4. Barker’s 1975 Paradigms – Pioneers and Paralysis

Paradigms are how the world makes sense to most of us. Paradigms are the thoughts and things we use to understand and interact with the world around us. Further, Paradigm Pioneers are people who challenge what we know to be the correct norms. Paradigm Paralysis is the condition when the old way cannot change.

All social, political, economic and technological change goes through the paralysis-pioneer cycle. A firefighter wearing their seat belt in moving fire vehicles is a perfect example of paradigm change. In some fire departments, failure to use a seat belt can now result in termination on the first offence. But we still see firefighters not wearing their seat belts. In January 2021, a firefighter fell out of the engine responding to an alarm when the vehicle turned a corner.

5. Deming’s 1980 System of Profound Knowledge

Deming’s system consists of four parts: appreciation of a system, knowledge of variation, theory of knowledge, and knowledge of psychology. He said, “The product is only as good as the process,” using mathematics to prove it. So, if you want a better product, meaning the best quality at the best price, you must make sure the human factors and engineering factors are aligned. All the stakeholders must have a common vision of what success means. The fire service application: Our fire service culture must promote that firefighters not wearing their seat belt is a “special cause” variation that is a defect to eliminate.

6. Schein’s 2010 Organizational Culture and Change

Culture is the combination of artifacts, espoused beliefs and underlying assumptions. A key feature of the Schein mode is that Underlying Assumptions will trump Artifacts and Beliefs when in conflict. For change to be achieved, individuals, groups and organizations must unfreeze, cognitively restructure their beliefs, and refreeze the new behavioral norm.

Fire service change in action: In 2015, the USFA published the National Safety Culture Change Initiative. In 2019, NIOSH included culture as a recommendation, for the first time, in report No. 2017-06. Recommendation #5: Fire Departments should ensure the fire service culture does not contribute to firefighter occupational injuries and fatalities when making decisions to ensure that both the fire service culture and departmental safety climate can be moved forward together in a common-sense, safety-oriented approach.

Understand the changing world around you

The human change paradox is that we impose change and resist change. But models and research can help us make sense of it all.

The theories discussed here have helped me understand myself and the world around me, even these recent struggles we have faced as a nation. Throughout my fire service career, I have been in all the positions on the bell curve, from “lager” because I did not drive the engine fast enough to innovator because I was the first firefighter to use a Nomex hood in the fire department. (I bought the Nomex hood at a 1973 fire conference. I was laughed at by my brother firefighters. Then some Squad firefighters ask me where I got it, they bought some, then no more laughs.)

I hope you can use the model personally and professionally to see where you are on any aspect of your life and why you are there. Being part of the norm is easy; it is challenging to be at either end of the process, but that is where you can find leadership, change, the future – and the “crazy” people.

“Live long and prosper” – Vulcan wisdom.