General

The success of a fire service radio system project hinges on the performance of the portable radio. If the portable radio has poor performance, the end-user relates it to the performance of the radio system as a whole. All the firefighter knows is that when the PTT was pressed the communications worked or did not work.

Manufacturers offer radios at different price points to meet market need. As with any other product, the options and performance levels increase with the cost. Usually there are three tiers of radios available. At the lowest level are nonruggedized radios meant for users who do not handle radios in a rough manner and do not operate in environmental extremes. The second level of radio is for the user who needs more reliability and performance features. The highest tier radios are focused on the public safety user. They offer the highest levels of performance and reliability and have the most options available. At this level, the radios often are submersible and have intrinsically safe options. Submersible radios are a very worthwhile option for the fire service, considering the possibility of radios getting wet or exposed to steam.

Ergonomics

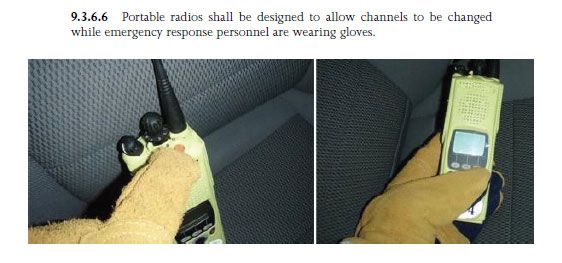

Today’s radios are an integral part of firefighting and a key component of fireground safety. The form and fit of the radios for firefighting has not improved much over the past decade. Buttons and knobs have increased in size as compared to the radios of the 80s and 90s, but firefighters have the same difficulties operating radios while in personal protective equipment (PPE). Radio knobs still cannot be manipulated with a gloved hand, even though it is required as a component of National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standard 1221, Standard for the Installation, Maintenance, and Use of Emergency Services Communications Systems.

|

|

The radios of today can be programmed with hundreds of channels or talkgroups. The large number of channels/talkgroups has made “hard switches” that correspond with a channel/talkgroup impossible. To select channels on radios with added channel capabilities requires liquid crystal displays (LCD) and “soft keys” to provide access. In firefighting, the LCDs are not readable in smoky environments and the soft keys cannot be pressed with a gloved hand. When programming the radio, take care to make firefighting radio channels easily accessible.

Environmental Technical Standards

Radios are designed to operate in environmental ranges. The harsh environment of firefighting is hard on equipment and personnel. To provide reliable communications, it is common to purchase ruggedized communications equipment. The technical specifications and testing protocols used to determine if a device is rugged can be confusing. Manufacturers use several testing protocols to determine if the device is “Public Safety Grade.” Some of the more common standards encountered are Military Standards (Mil Std) and International Electrotechnical Committee (IEC) standards.

IEC IP (Ingress Protection) Codes

IP codes are international standards that test for ingress protection into an electrical enclosure. Manufacturers use this code to rate intrusion against solid objects from hands to dust and water in electrical enclosures. The rating consists of the letters IP followed by two digits. The standard is intended to provide an objective testing protocol to reduce subjective statements such as “waterproof”. The first digit represents the size of the object that is protected against and the second digit represents the water protection. More detailed information on this standard can be found at www.iec.ch, International Electrotechnical Committee, IEC 60529.Mil Standards

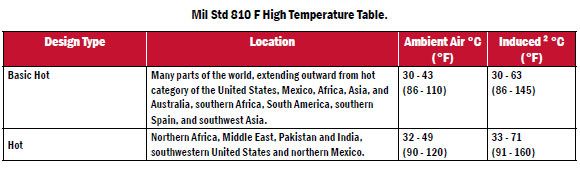

In the 70’s and 80’s radios were manufactured to various industry standards for ruggedness and technical stability. In the 90’s radio manufacturers adopted Mil Std 810 as a standard for reliability and ruggedness. Mil Std 810 was developed by the military to provide an environmental test protocol that would prove qualified equipment would survive in the field. Mil Std 810 is a test protocol written for the military environment not the firefighting environment. The specification sheets often reference a letter designation behind the Mil Std. The letter designation represents the revision level of the Mil Std being tested to. The latest revision is Mil Std 810 F. Earlier revisions of the Mil Std 810 were generic up to revision C. Subsequent revisions became more tailored to the actual environment the equipment would operate in. Manufacturers sometimes only perform specific test components of the Mil Std. For instance, an equipment specification may read “Mil Std 810 F for water, dust and shock resistance”. When we see Mil Std 810 we assume that the equipment is ruggedized and will survive the firefighting environment. We need only look to the temperature specification to see that this is questionable. Mil Std 810 F actually has two temperature specifications depending on where the equipment is to be used.

|

|

The table shown is the high temperature table from Mil Std 810F. A similar table is included in Mil Std 810 F for low temperatures. Most manufacturers test to the “Basic Hot” and “Basic Low” temperature levels. This temperature range is from approximately -30° C to 60° C (-22° F to 140° F). These temperature extremes do not replicate the environments that firefighters encounter.

National Institute of Standards and Technology Testing

NIST has performed testing on portable radios that more closely mimics the firefighting environment.

The results of these tests exposed the vulnerability of the portable radios to elevated temperature conditions, and emphasized the need to protect the radios when used in firefighting situations. Radios tested inside the turnout gear pocket showed that the turnout gear pocket was able to protect the radios and allow them to operate at the Thermal Class III temperature of 260 ºC. This contrasts with tests where the radios were exposed directly to the airflow, in which the radios did not survive at Thermal Class II conditions and beyond. In all but one test, the exposed radios were able to operate properly at the Thermal Class I temperature of 100 ºC, above the listed maximum operating temperature of 60 ºC. Failure of the electronics due to heating was not permanent for the radios. In all cases where the radio casing was not damaged, the radios regained normal operating function once they had sufficiently cooled. Permanent damage to the casing, such as difficulty turning knobs or pressing buttons did occur for some radios whose casings experienced melting. Permanent damage also occurred to the external speaker/microphones, especially due to the melting of the connecting cables.

The next step for this project is to work with the NFPA to develop a radio standard that would include requirements for the thermal testing of handheld radios.

How Many?

After defining the technical and operational requirements of the radio, the number of radios needed has to be determined. Departments have to identify who needs radios. A portable radio for each firefighter provides the highest level of safety. In addition to firefighters, radios for support and other fire department functions should be considered.

Additional guidance can be found in the following NFPA standards:

• NFPA 1561, Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System:- 6.3 Emergency Traffic.

- 6.3.1* To enable responders to be notified of an emergency condition or situation when they are assigned to an area designated as immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH), at least one responder on each crew or company shall be equipped with a portable radio and each responder on the crew or company shall be equipped with either a portable radio or another means of electronic communication.

• NFPA 1221:

-9.3.6 Two-Way Portable Equipment.

-9.3.6.1 All ERUs (Emergency Response Units) shall be equipped with a portable radio that is capable of two-way communication with the communications center.

What Type?

Since radios are tiered based on performance and ruggedness, there can be significant cost savings by buying high-tier radios for responders and the appropriate lower tiered radios for support staff.

|

|

• High-tier — High-tier radios should be provided to each firefighter. This level of radio gives the highest level of performance and reliability that radio manufacturers can provide. Within each tier there may be options that provide additional capabilities or functions. If using radios for emergency medical services (EMS) and fire functions, encryption may be required for operations with law enforcement agencies or to comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) requirements.

• Midtier — Midtier radios may be appropriate for users who do not enter into the firefighting environment. This type of radio would be a good choice for EMS functions. Again encryption may be required to meet HIPAA requirements.

• Low-tier — Low-tier radios are an option for some support staff. These radios provide communications for users who are not in harsh environments and may not need all the functionality of the higher tiered radios.

Fire Radio Features

Many features are available in modern radios. Like automobiles, stripped-down versions of radios are available, but when options are added the cost rises. To identify the desired features, focus and user groups can assist in developing the radio feature sets that meet user’s needs. Today’s radios are extremely flexible in programming features and the functions of buttons on the radio. Cooperation between the radio vendor and technical provider for your radio system will be instrumental in filtering through all of the programming parameters. Some of the newer features that increase firefighter safety are:

• Voice channel announcement — This feature uses prerecorded voice prompts to notify the firefighter what channel the radio is on as the channel select knob is moved.

• Emergency indications — Radios on the fireground receive an indication of emergency activations on the assigned channel.

• Personnel accountability — In new systems there are more radio ID numbers available. This makes itpossible for each radio to have an individual ID code enabling identification of the unit and specific position of the unit on an emergency activation. If tied to roster information in a computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system, identification of the individual firefighter is possible.

• Tones — Many radios use tones as an indication of trunked system access, out of range, repeater access, encrypted channel, and others. Use of tones may provide added awareness to the firefighter and, thus, increase safety.

For guidance on the minimum feature set a radio should have, refer to NFPA 1221 Section 9.3.6:

9.3.6 Two-Way Portable Equipment.

9.3.6.2 Portable radios shall be manufactured for the environment in which they are to be used and shall be of a size and construction that allow their operation with the use of one hand.

9.3.6.3 Portable radios equipped with key pads that control radio functions shall have a means for the user to disable the keypad to prevent inadvertent use.

9.3.6.4 All portable radios shall be equipped with a carrier control timer that disables the transmitter after a predetermined time that is determined by the authority having jurisdiction.

9.3.6.5 Portable radios shall be capable of multiple-channel operation to enable on-scene simplex radio communications that are independent of dispatch channels.

9.3.6.6 Portable radios shall be designed to allow channels to be changed while emergency response personnel are wearing gloves.

9.3.6.7 Single-unit battery chargers for portable radios shall be capable of fully charging the radio battery while the radio is in the receiving mode.

9.3.6.8 Battery chargers for portable radios shall automatically revert to maintenance charge when the battery is fully charged.

9.3.6.9 Battery chargers shall be capable of charging batteries in a manner that is independent of and external to the portable radio.

9.3.6.10 Spare batteries shall be maintained in quantities that allow continuous operation as determined by the authority having jurisdiction.

9.3.6.11 A minimum of one spare portable radio shall be provided for each 10 units, or fraction thereof, in service.

Portable Radio User Guide

Users and their behaviors have an impact on the effectiveness of fireground communications. Human factors, such as the way we speak and organization of reports, affect communications. Technical factors obviously have an impact on fireground communications. Like any other technology, users need to know the limitations of the technology and how to use the tool appropriately.

Human Factors

When we talk on the radio, each of us subconsciously performs a process before we speak. Managing this process will provide more effective communications.

• Organization — Before speaking, formulate what information is being communicated and put the information in a standardized reporting template. For instance, a standard situational report might contain Unit ID, location, conditions, actions, and needs. This method forces users to fill in the blanks, answer all the necessary questions, and filter out unneeded information.

• Discipline — Often, ICs are overwhelmed by excess information on the radio. Radio discipline on the fireground will help to determine if information needs to be transmitted on the radio. If face-to-face communications are possible between members of a crew and the information is not needed by the IC, don’t get on the radio.

• Microphone location — Placing a microphone too close to the mouth or exposing the microphone to other fireground noise may result in unintelligible communications. When transmitting in a high-noise environment, shield the microphone from the noise source. Hold the microphone a couple of inches from the mouth or, when speaking through a SCBA mask, place the microphone near the voice port on the facepiece.

• Voice level — When speaking into a microphone use a loud, clear, and controlled voice. When users are excited, the speech often is louder and faster. These transmissions often are unintelligible and require the IC to ask for a rebroadcast of the information, resulting in more radio traffic on the channel.

Managing these human factors will have a positive impact on fireground communications. Reporting should be complete, necessary, and in a controlled, clear voice. These actions will reduce the amount of repeat transmissions on the fireground, reducing air time.

Technical Factors

In some cases communications problems are caused by a technical issue. Users need to recognize technical problems and take corrective action to improve communications. Radio users often blame the radio or system for coverage problems. In many cases user actions can improve communications.

Position and Radio Location

As we know, firefighting often places firefighters in challenging environments forcing them to crawl on the floor. The optimal position for a portable radio transmission is at head height with the antenna in a vertical position. The photo below shows a firefighter on the floor. The radio is against the body inside of the radio pocket on the turnout coat. Some of the transmitted energy is absorbed by the body, and the antenna is in a horizontal position. This results in a poor radiation pattern and a reduction in range of the radio. Moving to a location where the firefighter can sit up may improve communications, if transmissions from the prone position are not heard.

Many users do not use a radio pocket or case. In the middle photo above, the Company Officer’s (CO’s) radio (left) is clipped to the exterior of the coat, while the firefighter’s radio is protected. The tradeoff is that the radio is exposed to heat and steam but is in a better transmitting position. When unprotected, the radio may fail to operate when needed. Radio cases with shoulder straps provide little protection and are an entanglement hazard when worn on the exterior of turnouts.

Coverage

When communicating on the fireground some areas of a building may be difficult to communicate from. When encountering these areas, move to a location where communications are possible. Areas that may improve communications are near windows and doors.

Accessories

Many accessories are available for radios. Use of accessories that protect the radio from heat and steam allows the radio to operate in high heat environments. Each user group may have specific working conditions that require some accessories to make radio communications easier. Common accessories include carrying cases, speaker microphones, ear pieces, chargers, battery types, and optional antennas. User and focus groups will help identify the accessories needed to support your department’s needs.

Summary

Many factors contribute to the success or failure of fireground communications. Some are human factors that affect the way information is processed and communicated. Processing and communicating information in a standardized manner assists in managing information and the amount of traffic on the radio. Speaking with a loud, clear, and controlled voice will reduce the amount of repeat radio traffic on the fireground. Technical factors require recognition of the problem and some corrective action by the user to improve communications.

The portable radio equipment is what the firefighter sees and has the most impact on the perceived performance of a system. Inclusion of user groups in the selection process of the portable radios and accessories provides insight into the functions and features needed. Determine the size of the radio fleet and the users who need radios. This will assist in classifying each user type and the radio tier needed for each user classification. Selecting the correct tier radio for the target user is a way to contain cost and provide reliability for users on the fireground. While today’s radios provide reliable communications, they are not manufactured for the extreme environments of the fire service. When selecting radios, consider features that increase firefighter safety. The minimum feature set for firefighting portables can be found in NFPA 1221.

NEXT SECTION - Trunked radio systems

|

|