When writing about the management of emergency incidents, I find myself – as well as other writers – including this verbiage, “Develop an incident action plan.”

Why? Because developing this plan, successful communicating their part to fire officers and monitoring progress towards its completion are three of the key responsibilities for the incident commander.

So, whether you’re an experienced incident commander or a new officer who’s still gaining experience, there are a few basics for fulfilling this critical responsibility.

The incident commander first develops an action plan in their own mind. And since the other fire officers responding to the incident are not mind-readers, it’s incumbent upon the commander to articulate what’s in their mind to those officers so that meaningful action takes place to accomplish the plan. This process is the foundation for running the incident operations in a safe and effective manner.

All fire officers must be proficient at developing an incident action plan. This is especially important for company-level officers, who will typically be the initial incident commander, for a couple of reasons.

First, they must get the incident management system started, have a plan and get fire companies committed to actions that support their plan.

Second, having a plan (probably in their head at the time) will enable them to accurately communicate the information necessary to transfer command to a later-arriving fire officer, usually a command officer.

The components of an IAP

It’s important that all fire officers know how to use the standard process for developing an incident action plan. By using this standard process for both training activities and actual emergency management, officers will have a common expectation for how things will run.

This makes for much better communication of an action plan’s elements between the incident commander their fellow fire officers during an emergency incident. These are the five elements for developing and communicating your action plan to those officers.

1. Conduct size-up

NIOSH investigation of firefighter fatalities has regularly identified lack of a complete 360-degree fireground assessment by the incident commander as a contributing factor in firefighter deaths. The key questions that the incident commander must answer when they arrive on the scene are:

- What has happened prior to my arrival?

- What is continuing to happen as time goes by?

- What will continue to happen without our intervention?

Next, the commander needs to quickly assess what interventions will be possible given the assessed situation. The International Association of Fire Chiefs first published its “10 Rules of Engagement for Structural Firefighting” in 2008. The model was based upon two key concepts, acceptability of risk and risk assessment.

Acceptability of risk

- No building or property is worth the life of a firefighter.

- All interior firefighting involves an inherent risk.

- Some risk is acceptable, in a measured and controlled manner.

- No level of risk is acceptable where there is no potential to save lives or property.

- Firefighters shall not be committed to interior offensive firefighting operations in abandoned or derelict buildings.

Risk assessment

- All feasible measures shall be taken to limit or avoid risks through risk assessment by a qualified officer.

- It is the responsibility of the incident commander to evaluate the level or risk in every situation.

- Risk assessment is a continuous process for the entire duration of each incident.

- If conditions change, and risk increases, change strategy and tactics.

- No building or property is worth the life of a firefighter.

These rules are not meant to be a step-by-step process. Rather, fire officers should continually study these rules, understand them and commit them to memory. The IAFC’s rules of engagement are designed to help mold the way an incident commander acts.

2. Determine mode of operation

Based upon their size-up of the situation, the incident commander must decide upon the appropriate mode of operations for the incident.

They can choose rescue mode if there is a significant life safety hazard to building occupants that requires their removal by firefighters. The commander’s tactical assignments will be focused on supporting those rescue operations prior to an aggressive attack on the fire.

They can choose an offensive mode. Here, the commander commits firefighting personnel and equipment to interior structural firefighting operations with the intent to quickly bring the fire under control.

They can choose a marginal mode. Here, the commander’s size-up leads them to believe that an interior fire attack can be successfully only if accomplished within a limited window of opportunity. Fire officers given tactical assignments in the interior must understand that they are on a short leash time-wise to accomplish their tactical objectives.

When selecting this mode of operation, the commander must closely monitor the situation to ensure that quick progress is being made. If not, they should be prepared to withdraw personnel from the interior and transition to the defensive mode.

The defensive mode is picked when the commander’s assessment is that the situation is not safe for conducting interior fire attack operations. Their goals and objectives will focus on protecting any exposures and extinguishing the fire from exterior positions.

3. Set incident goals

What must the commander accomplish, with the resources available, to resolve the situation? In developing their incident goals, they should follow a set of three incident priorities.

1. Life safety. Are there occupants in need of rescue or protection from the fire?

2. Incident stabilization. What needs to happen to make the situation better?

3. Property conservation. What needs to happen to prevent further loss of property after the incident has been stabilized?

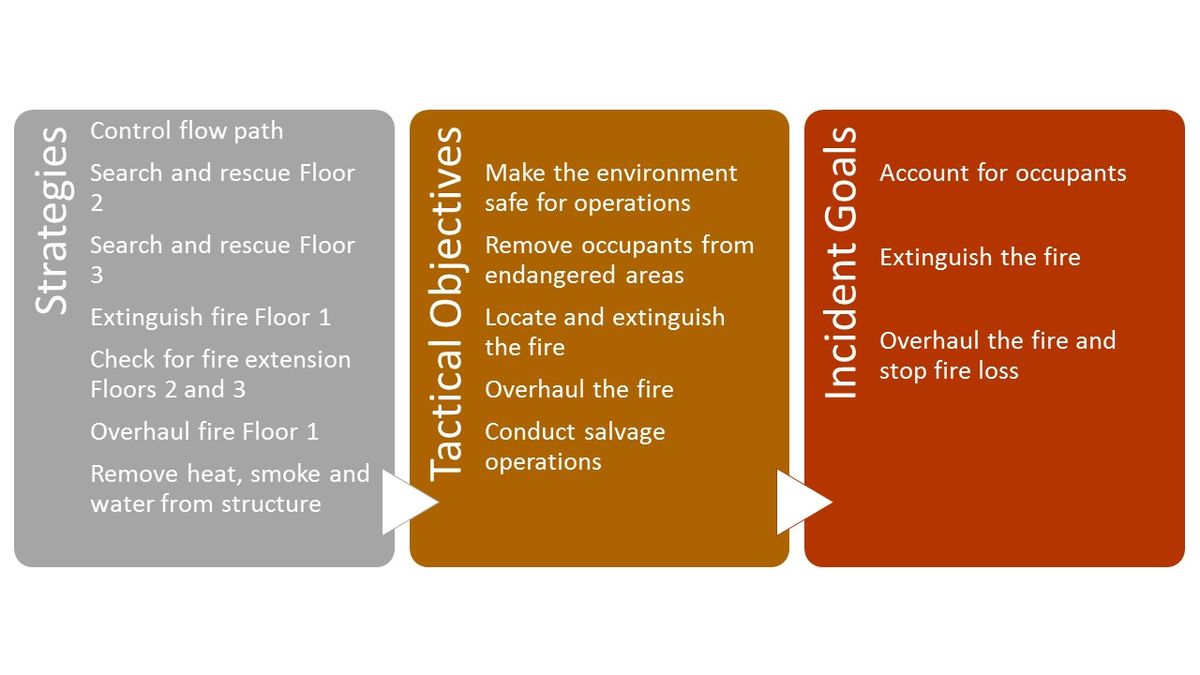

An example of incident goals, in priority order, for a structure fire in a two-story, single-family dwelling with fire showing from a kitchen window on Side C at 2 a.m. would be: account for occupants, extinguish the fire, overhaul the fire area and stop property loss.

This part of the plan is your incident command scorecard. As your fire companies complete their tactical objectives, you should be able to check off each goal on your plan. Complete all the goals and you’ve managed the operation to a successful conclusion.

4. Determine the tactical objectives necessary to achieve the incident goals

What are those things that fire companies must accomplish to achieve the incident goals? Some examples of tactical objectives are:

- Control the flow path in the structure.

- Remove occupants from endangered areas.

- Locate and extinguish the fire.

- Overhaul the fire.

- Conduct salvage work.

This is another scorecard section of your plan. By tracking the completion of tactical objectives by assigned resources, you’ll ensure that no tactical objective gets overlooked.

Feedback from fire officers assigned to complete tactical objectives is critical, especially if they are not able to complete their objective or if they encounter another problem.

5. Set strategies to accomplish the incident objectives

In this final step for developing your incident action plan, you’re matching up your available resources with the tasks necessary to accomplish your tactical objectives. Here are three examples of what this might look like.

- “Engine 1 from command. Advance 1¾-inch attack line through door, Side Alpha. Your assignment is fire control on floor 1 to protect the interior stairwell.”

- “Truck 1 from command. Your assignment is to control the flow path to support search and rescue on floors 2 and 3.”

- “Engine 2 from command. Advance 1¾-inch attack line through door, side Alpha. Your assignment is search and rescue on floor 2.”

Every tactical objective should have a resource assigned to it and a fire officer responsible for accomplishing it.

Figure 1. A well-developed IAP has strategies driving the accomplishment of tactical objectives which in turn leads to the accomplishment of incident goals.

Developing an incident action plan is a critical incident command skill and, as with any skill, it must be practiced to develop proficiency. And it requires continued practice, using a variety of emergency scenarios, to maintain that proficiency.